Once again I (happily) find myself busy with speaking engagements, including two next week. First, on Friday, November 18 (which will be the evening of November 17 on the eastern seaboard of the US) I am giving a (remote) lecture at Fudan University in Shanghai entitled ‘The Persian Pharaohs: Kingship and Imperialism in Achaemenid Egypt.’

My abstract for the talk is admirably concise and suitably vague:

This lecture examines how the Achaemenid Persians used the Egyptian institution of kingship to rule Egypt during the 27th Dynasty, ca. 526-404 BCE. Rather than destroying or marginalizing the pharaonic office, the Persian kings, beginning with Cambyses, assumed the role of Egyptian king. This served two purposes. First, it supported Achaemenid ideology, which depicted the Persian ruler as ‘king of kings.’ For this ideology to be meaningful local institutions of kingship had to remain intact. Second, it provided a means of controlling Egypt without having to create a new administrative framework. In essence, the Persians inserted themselves into the highest level of Egyptian political authority and did not interfere with the rest. Yet the Persian kings went beyond simply filling the role of pharaoh and actively used Egyptian institutions, such as temples, to further their own imperial goals, such as controlling the Western Desert and acquiring silver for tribute. This practice accounts in significant part for the relatively invisible nature of Achaemenid rule in Egypt.

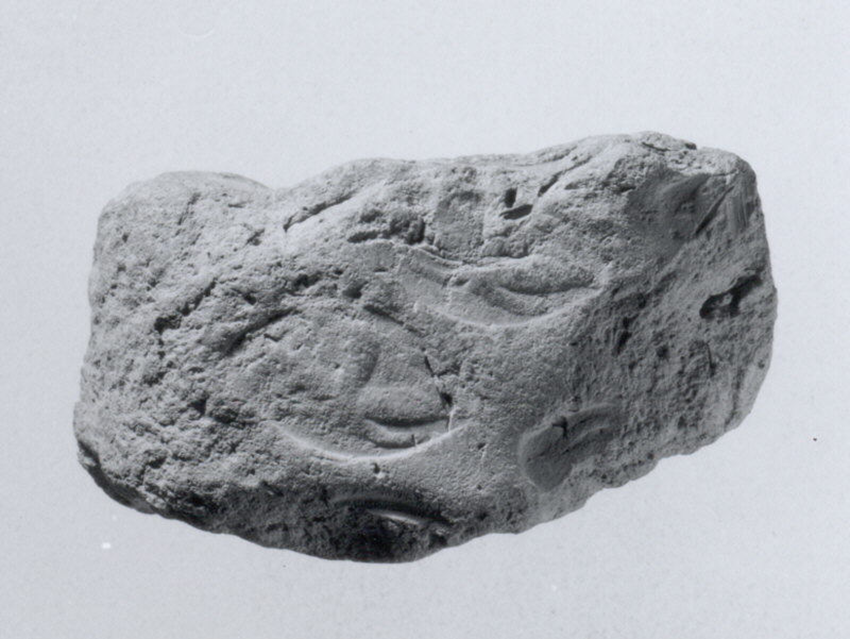

Second, on Saturday, November 19 I will give a talk at the ASOR Annual Meeting in Boston entitled ‘Greek Style and the Problem of Parthian Art,’ as part of a session on ‘Style and Identity in Ancient Near Eastern Art.’ My long abstract for the talk is here. Suffice to say, my talk considers why Parthian art might look the way it does. As a teaser, here’s one of the objects I plan to discuss:

If that doesn’t pique your curiosity, then we probably shouldn’t be friends.

My third talk is on December 8 or 9 at the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters in Copenhagen, at a conference entitled ‘Palmyra in Perspective: Reflections on a Critical Decade of Scholarship (2012-2022).’ My paper is called ‘Palmyra and the Problem of Parthian Art’ (I detect a theme in my lecture titles).

Once again, my abstract is sufficiently brief to post here:

What can Palmyra tell us about Parthian art? The city was never under Parthian control, and previous scholarship on Palmyrene art has focused mainly on its interactions with Roman art and its influence on the art of Dura-Europos, its neighbor to the east. Yet it is undeniable that there are convergences in style and iconography between Palmyrene art and the art of the Parthian period in Mesopotamia and western Iran. These include frontal renderings of the human form, the presence of the Iranian riding costume and reclining banqueters, and even the treatment of bodily proportions. Rather than focusing on origins of certain motifs or the artistic influence of one cultural entity upon another, it is more useful to consider what these convergences might tell us about the nature of Parthian imperialism. Following Mikhail Rostovtzeff, I argue that Parthian art was a cogent – if currently unknowable – phenomenon, that affected other artistic traditions within and adjacent to the empire as people forged putatively ‘Parthian’ identities for themselves. In the case of Palmyra, ‘Parthian’ was one of many identities that the people there considered to be useful, appropriate or otherwise desirable, and this is reflected in the art they produced. Palmyra, therefore, is an essential part of the solution to the problem of Parthian art.